#7: Git for Open Source Development

1. Recap

This talk assumes knowledge of Abi’s git talk from last semester; to familiarize yourself with git basics, please refer to her talk!

A note about .gitconfig; I’ve modified mine a bit so if you follow along you may not see the exact same things I’m seeing. Here are the relevant bits:

[user]

name = Jesse Spielman

email = jesse.spielman@gmail.com

[core]

autocrlf = input

excludesfile = ~/.gitignore_global

pager = "less -FRSX -#5"

editor = vim

[alias]

co = checkout

st = status --short

[color]

ui = auto

branch = auto

diff = auto

interactive = auto

status = auto

shortlog = auto

[color "branch"]

current = yellow bold

local = yellow

remote = red

[color "diff"]

meta = yellow bold

frag = magenta bold

old = red bold

new = green bold

whitespace = green reverse

[color "status"]

added = yellow

changed = green

untracked = cyan

[diff]

pager = "less -FRSX -p '^diff.*'"

tool = "vimdiff"

algorithm = histogram

[format]

xpretty = "format:%C(yellow)%h %C(blue)%an %C(green)%ar %C(reset)%s%n%w(70,4,4)%C(reset)%-b"

[push]

default = simple

[merge]

log = true

tool = "vimdiff3"

[mergetool "vimdiff3"]

cmd = vim -f -d -c \"wincmd J \" \"$MERGED\" \"$LOCAL\" \"$BASE\" \"$REMOTE\" \"+:0/<<<.*\\|===.*\\|>>>.*\"

[rerere]

enabled = 1

[credential]

helper = cache --timeout=3600

[pull]

rebase = true

[init]

defaultBranch = main

[filter "lfs"]

clean = git-lfs clean -- %f

process = git-lfs filter-process

required = true

smudge = git-lfs smudge -- %f

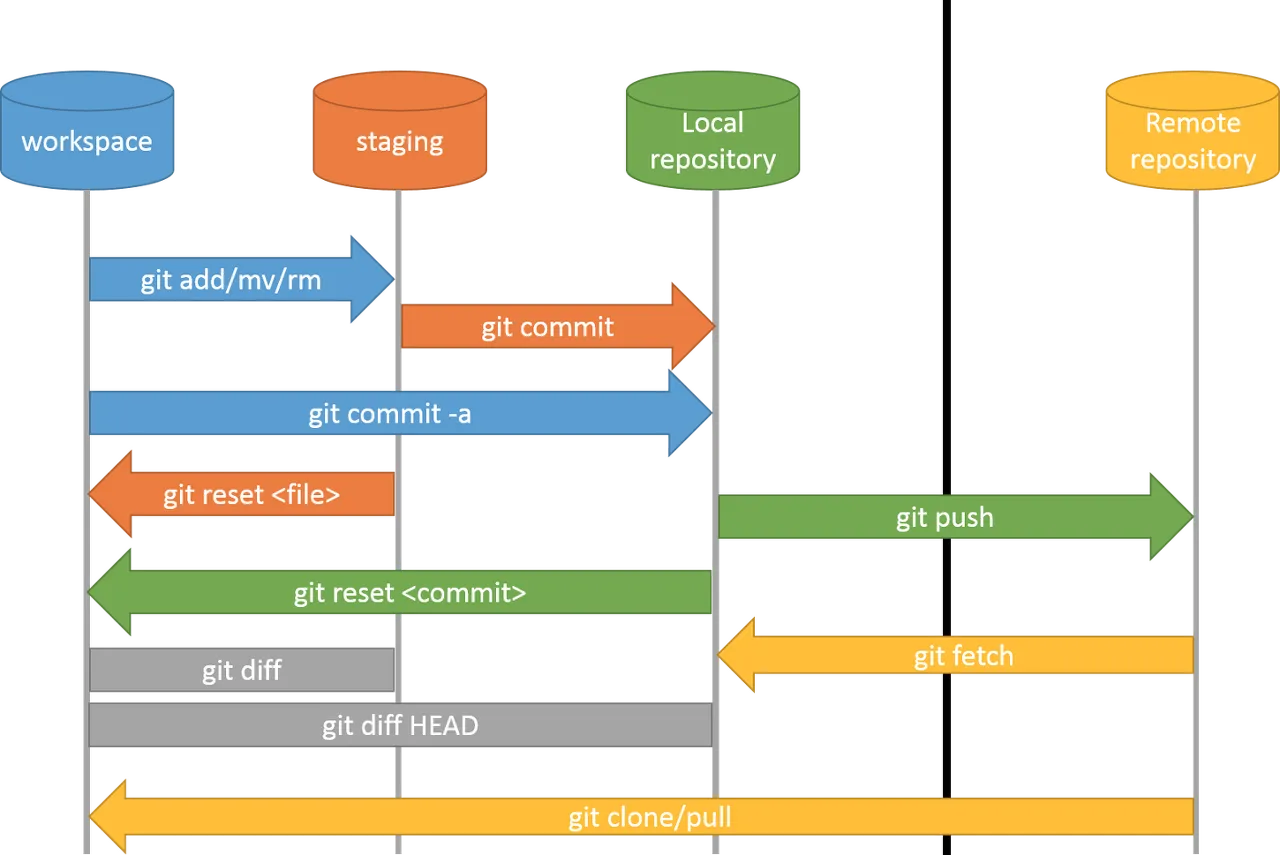

To briefly summarize Abi’s talk, lets look at this graphic:

Remember also that git has many uses:

- Ultimate Save System

- Quasi Backup System

- Collaboration Tool

- Deployment Mechanism

With that in mind, lets dive into some of the more interesting, advanced stuff!

2. Viewing History

First, lets talk about ways of viewing history. This won’t seem important now but will be super handy shortly when we start manipulating history.

Lets clone a repo, say, the one for this website:

git clone https://github.com/afnom/missing-semester.git

You can also add a remote that represents the original MIT website with git remote add mit https://github.com/missing-semester/missing-semester; don’t forget to run git fetch --all after!

Do we have an intuition for what this history will look like?

Now, lets try visualizing the history using:

git logorgit show $HASH?- How about via

gitk/gitk --allandtig/tig --all? - Finally lets look at

git blame/ fugitive’sGblame.

Takeaways:

- Remember: a commit should be an entire idea

- ideally everything works before and after a commit.

- First line of commit vs rest of commit as Abi pointed out.

- Super useful to ‘go back in time in the project’ in terms of when things changed, by who etc.

- Neat to see where we are relative to the original project

- Can see how the original developers have diverged from us

- gitk lets us run actions on commits…

- creating branches

- resetting etc

3. Managing History

Version control systems seem to want you to:

- Do a specific task

- Commit it

- Move onto the next commit

But we know that’s not always how we work! We might work for a few hours and then want to commit our work but still in logical ‘good’ commits rather than one giant ‘commit stuff’ commit.

The magic -p flag

Usually history refers to commit but I mean it more generally here – let me show you an example.

Here, I’ll demo the lovely -p flag for git add, git checkout and git reset

Hopefully now it’s more clear why git commit -a is bad – it strips git of the power of the staging area! Building commits up from bits of work allows us to produce more coherent and useful commits.

Having looked at histories above, maybe it’s more clear now why producing good commits is the key to making git useful, especially in a collaborative eg team project context.

Don’t forget to try to keep the first line of a commit message <= 50 characters and expand if needed after two newlines.

Rewriting history

Beyond merging branches (which was covered last time) and simply adding new commits, there are powerful tools in git for managing existing history:

- undoing commits with

git revert - amending commits with

git commit --amend - Stealing commits using

git cherry-pick - full blown history manipulation with

git rebase -i

Remember: you almost never want to manipulate history that’s already been pushed

Resolving Merge conflicts

Merge conflicts occur when git needs your help to combine commits. Git is pretty clever about this and so this usually only happens if conflicting changes happen in the same area of a particular file.

I’d like try to step through a merge conflict:

- Perhaps to bring in the enhancements made by MIT’s version of the site?

- Or simply to merge two different branches…

4. Collaboration

Now that we understand a bit more about history and how to interact with it, lets talk about collaboration. Remember that collaboration can happen if people are git commit -a-ing all over the place but it’s helpful and kind and thoughtful to your collaborators (or your future self!) to make good commits!

Refresher on Remotes

- Until this point we’ve only been thinking locally but lets bring back the concept of remotes and therefore collaboration.

git remotevs poking around in.git/config- Remember:

git pull=git fetch+git merge - force pushing and why it is bad

- Remotes don’t always mean collaboration; if you’re the only developer force pushing to a remote isn’t necessarily bad.

Git collaboration tools

Having remotes that are available to you and your collaborators means you’ll be able to share history.

Since everyone on a team has access to the same remotes (and so long as they are remembering to keep their own contributions tidy and resolve the occasional merge conflict), developers can easily collaborate.

github and gitlab are the two most popular git services that are out there but you can also self host with alternatives like gogs and gitea.

Collaboration Modes

There are a number of ways to organize collaboration; one method is just give everyone read/write access to the repo as we do for the missing semester website. Note that non-ms organizers won’t have permission to write to the repo so even though they can clone the repo, they can’t push back their changes.

Another method of collaboration is pull requests; the github docs say:

These are useful in the case where:

- you want to let a team you may not be on about an improvement or a fix you’ve found / made

- your team wants there to be a formal process w/ discussion for integrating all changes, say for junior developers?

I’ll demo this now with the help of a MS-organizer in the audience?

Note also the ‘edit this page’ button at the bottom of the page…

CI / CD

CI (Continuous Integration) and CD (Continuous Delivery or Deployment) are a modern technique provided natively by services like github (via Github Actions) and gitlab that allow actions to be performed based on events in a repo’s development cycle, eg on git push

According to Wikipedia:

- Continuous integration: Frequent merging of several small changes into a main branch.

- Continuous delivery: When teams produce software in short cycles with high speed and frequency so that reliable software can be released at any time, and with a simple and repeatable deployment process when deciding to deploy.

Each service offers comparable services as explained in their documentation:

With CI/CD you can do things like:

- Automatically test code before it is deployed

- Deploy code when a certain branch is pushed (as with the MS website)

- Notify users etc

Basically anything you can do with code you can now tie into the git lifecycle.

5. Final thoughts

Some closing thoughts / odds and ends / stuff there may not have been time for.

git ls-filesgit stash- More about

.gitignore/ ‘global ignore’ - Managing binary files with

git-lfs - Common git troubleshooting steps / error messages

- What is detached head state

- What to do if you commit sensitive information?

- Reminder to check out git koans

- Consider the politics / policies of your git hosts, eg github

Licensed under CC BY-NC-SA.