#7: Git for Open Source Development

1. Introduction

This talk assumes knowledge of Abi’s Git talk from earlier this semester - prior to the talk, I would highly recommend refreshing your knowledge on Git itself just to make following along easier.

This talk covers a bit more about using Git for contributing to open source, one of its most popular uses to date. Sites like GitHub and Gitlab have connected millions of developers and nourished numerous open-source projects that have shaped the software landscape that we know today. According to GitCharts (https://gitcharts.com/), a site that tracks GitHub’s statistics, there are over 220 million public repositories, with 150,000 created each day and 450,000 forks created each day too. On June 4th 2018, Microsoft announced its acquisition of GitHub for $7.5 billion dollars (in stock), reinforcing the company’s stance on open source development - without GitHub’s impact, it’s entirely possible that a competitor like Gitlab would’ve taken the torch GitHub currently holds and ran with it, but it’s also not out of the question for the software landscape we know today to look incredibly different.

Due to its prosperity, this lecture will focus largely on GitHub and the tools it provides to developers, which should help put into perspective how it’s shaped open-source development throughout its reign. Thus, if you choose to follow along, be sure to have a GitHub account, and if you’re a student, you can take advantage of GitHub’s education pack, a pack that gives you access to JetBrain’s innovative IDEs, free domain names provided by Namecheap, name.com or .TECH, and if you choose to go down the route of payment processing for a project you have, waived transaction fees on Stripe.

You can read more about the Education pack here: https://github.com/education

We’ll be focusing on both ends of open-source development, from making contributions to open source projects to maintaining your own repository for contributions. As a demo, we’ll open a pull request to our MS repository, writing our name to the guestbook.

Ways of Contributing and How to Start

First of all, let’s start off with how contributions look on GitHub. Perhaps contrary to common belief, contributions on GitHub are not limited to contributing code through PRs - you can submit issues, review other developers’ code or even contributing to documentation if you’re not very confident with coding.

Some repositories will make use of a “good first issue” label, which will indicate what issues may be good for first-time contributors to tackle. You can filter by that label and see what issue stands out to you, or has not been resolved yet.

Whilst the Missing Semester repository (UoB’s version) doesn’t make use of issues, other repositories like CSS’ website use them, so if you’re looking to start somewhere, don’t be afraid to take a look :)

2. Creating a fork

Creating a fork is relatively simple on GitHub and even other sites. There’ll often be a “fork” button that you can simply press:

Once you click on this button, you’ll be presented with a screen to name your fork, a description of it and whether it copies the main branch or not. Generally, this is fine to keep enabled, unless you look to contribute to a different branch on the main repository.

Once created, you’ll then be able to clone your fork to work on it locally like a repository you’ve created yourself.

Updating your fork with upstream

If you’re updating software that has been abandoned, it’s unlikely that you’d need to update your fork to be up to date with the original repository. However, if the original repository is still being maintained and updated, you may choose to update your fork with it. In this context, the original repository you forked from is known as “upstream”.

GitHub and some other sites may have a simple “sync” button to do the update work for you, but it’s good to know how to manually do this, in case upstream commits break things in your fork. Some forks will have PRs opened to bring them up to date with their upstream.

In the command line, add a new remote called upstream:

git remote add upstream https://github.com/afnom/missing-semester

<<<<<<< HEAD

=======

From there, fetch from upstream to ensure you’re up to date:

git fetch upstream

> remote: Counting objects: 75, done.

> remote: Compressing objects: 100% (53/53), done.

> remote: Total 62 (delta 27), reused 44 (delta 9)

> Unpacking objects: 100% (62/62), done.

> From https://github.com/afnom/missing-semester

> * [new branch] main -> upstream/main

Switch to your fork’s main branch (with main being the name of your main branch - it may vary):

git checkout main

Then, you can merge with upstream:

git merge upstream/main

> Updating 34e91da..16c56ad

> Fast-forward

> README.md | 5 +++--

> 1 file changed, 3 insertions(+), 2 deletions(-)

There, you’ve updated your fork!

3. Committing Code with Visual Tools

You’ve been able to learn the foundations of Git itself, but it may be difficult to remember individual commands, or exercise more control over what code you commit - thus, you may choose to use more visual tools to commit code.

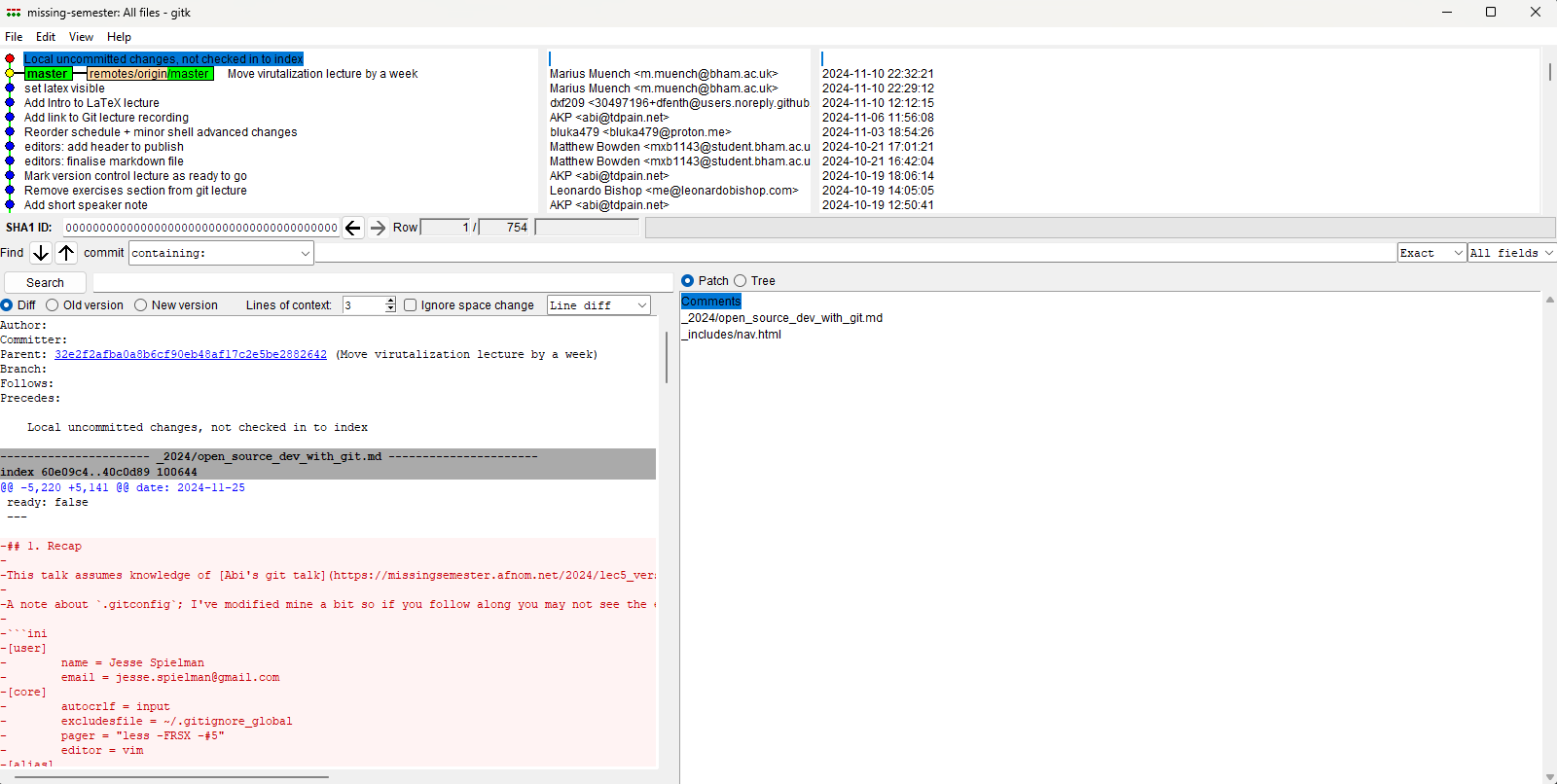

A lot of modern IDEs will have some kind of integration with Git, such as IntelliJ or VSCode. However, there may be other

visual tools that you choose to use instead. For example, I used GitHub Desktop when

I first started out. There’s also the gitk command, which is provided with Git itself. If you run the command within a

folder hosting a repository, it’ll open up a window that looks like this:

gitk is only for viewing commits rather than making them, and is very verbose - so it may be better for reviewing the

finer details of commits in a GUI.

4. Submitting a Pull Request

As mentioned prior, you’ll often make a fork to contribute to the original work - and that’s where pull requests come in. They tend to have different names across different sites, since it’s not necessarily a Git feature - Gitlab calls them merge requests and Bit Bucket also calls them pull requests. Sometimes developers only address them as PRs as a shorthand, which I will do as well.

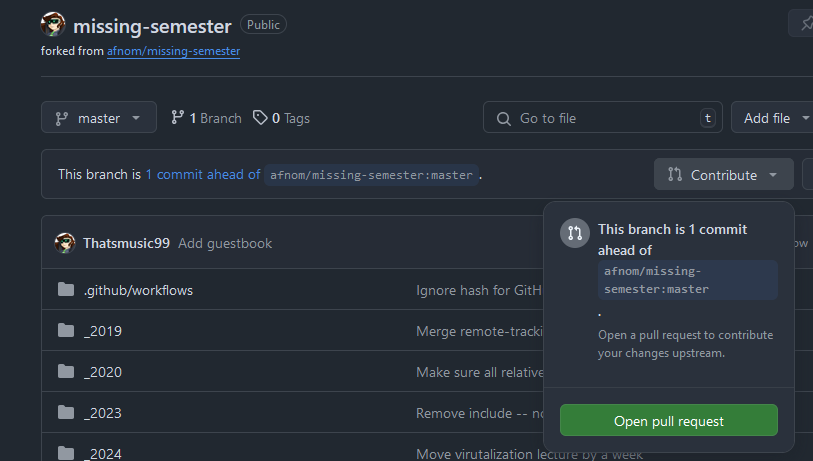

Once you’ve pushed your code, go to the main page of your fork, and check the “Contribute” button where it mentions your branch being ahead of your upstream repository:

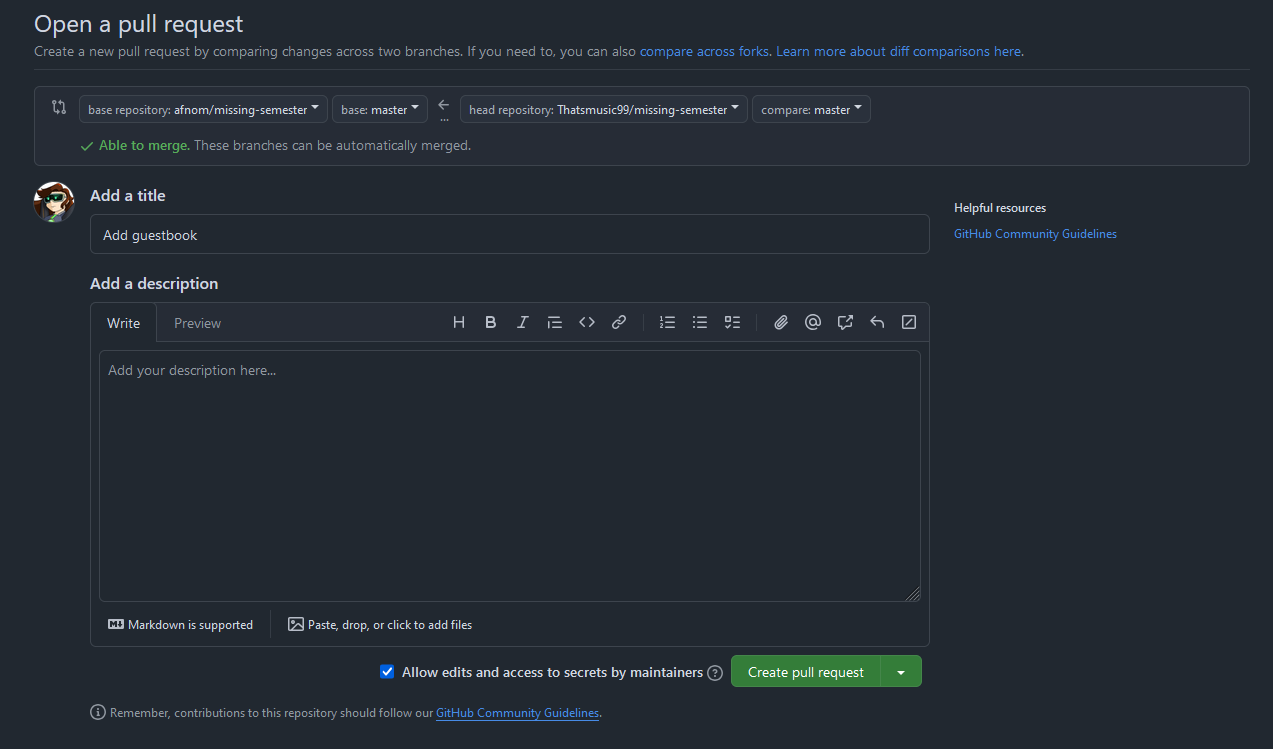

Then, click the “Open pull request” button. GitHub will then prompt you for the title of the PR, a description of what the PR does, and the branches to merge into/from.

If you see the small dropdown arrow next to “Create pull request” too, you can create a pull request as a draft, meaning that you’ve not completed your work yet, but can accept early review from maintainers or other contributors.

Best Practices

When making pull requests, different projects will have different ideals or requirements - and it extends to more than just making a good title and description. Here’s a quick list of what you may find:

- Some repositories will not allow you to merge from your main branch.

- Ideally, it would come from a non-main branch where all of your work for that PR is focused.

- Some repositories may also not let you make a PR from a fork under an organisation.

- You may remember the “Allow edits and access to secrets by maintainers” option? It doesn’t apply to organisation forks. By consequence, project maintainers who want to edit your PRs to rebase or resolve nitpicks will ask for you to do them instead.

- PRs need a specific scope, e.g. if you intend on fixing a bug, it’s only that bug you fix, rather than some formatting changes too.

- In addition to the above, depending on what is covered, PRs would ideally not be too big. Otherwise, they become too

cumbersome for maintainers to review.

- They also increase the likelihood of complex merge conflicts that are a headache to resolve.

- Some repositories may require an issue to be opened before making a PR, which the PR then can link back to. This is often for maintainers to give their stance on the issue and what can be done next.

Merge Conflicts

After submitting your pull request, it’s likely that other PRs will be accepted and merged in, or the main codebase is changed over time. If those changes alter what your PR covers, that can result in merge conflicts, which maintainers may request for you to resolve in order for them to accept the PR. Some simple ones can be resolved within GitHub - however, more complex ones will have to be resolved locally.

Let’s not only take an example, but make a merge conflict. I have the guestbook, and it currently looks like this after switching to main:

git checkout main

---

layout: lecture

title: "Guestbook"

---

This guestbook was made for those participating in the "Git for Open Source Development" lecture in November 2024, to

demonstrate opening a pull request and contributing to an open-source project.

And I have a branch (add-holly-to-guestbook) to add myself:

git branch add-holly-to-guestbook

git checkout add-holly-to-guestbook

With the guestbook content being:

---

layout: lecture

title: "Guestbook"

---

This guestbook was made for those participating in the "Git for Open Source Development" lecture in November 2024, to

demonstrate opening a pull request and contributing to an open-source project.

- Holly, 4th Year MSci Computer Science

However, let’s say someone else makes some changes to the guestbook content, and it ends up in main:

---

layout: lecture

title: "Guestbook"

---

This guestbook was made for those participating in the "Git for Open Source Development" lecture in November 2024, to

demonstrate opening a pull request and contributing to an open-source project. Pls be nice

aaaaaa

a

a

Once I attempt to merge add-holly-to-guestbook into main:

git checkout add-holly-to-guestbook

git merge main

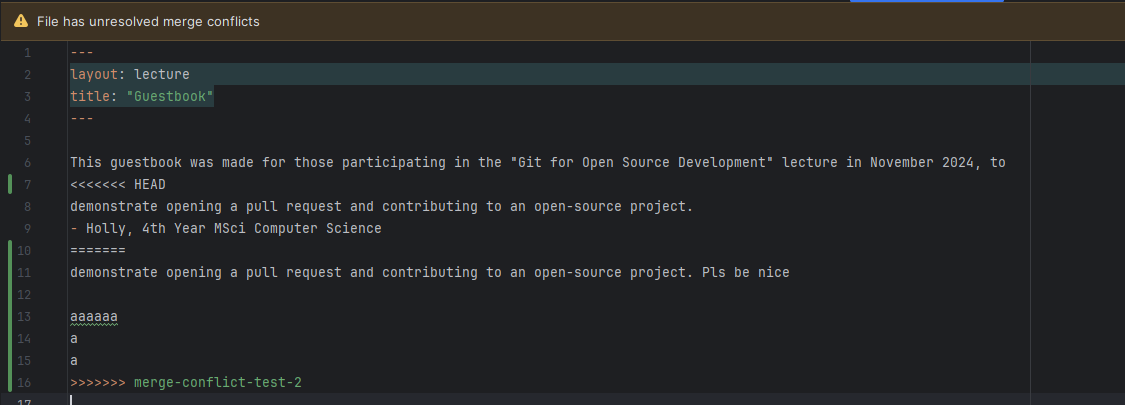

It results in something that looks like this:

Note: The conflicting branch here is

merge-conflict-test-2- in our example, this would bemain.HEADis also a stand-in foradd-holly-to-guestbook- it’s just a slight difference in how I produced the conflict.

This is a merge conflict. This may look scary at first, and there is reason behind the chaos it spits out - here’s the output we want to focus on:

<<<<<<< add-holly-to-guestbook

demonstrate opening a pull request and contributing to an open-source project.

- Holly, 4th Year MSci Computer Science

=======

demonstrate opening a pull request and contributing to an open-source project. Pls be nice

aaaaaa

a

a

>>>>>>> main

>>>>>>> upstream/master

From there, fetch from upstream to ensure you’re up to date:

git fetch upstream

> remote: Counting objects: 75, done.

> remote: Compressing objects: 100% (53/53), done.

> remote: Total 62 (delta 27), reused 44 (delta 9)

> Unpacking objects: 100% (62/62), done.

> From https://github.com/afnom/missing-semester

> * [new branch] main -> upstream/main

Switch to your fork’s main branch (with main being the name of your main branch - it may vary):

git checkout main

Then, you can merge with upstream:

git merge upstream/main

> Updating 34e91da..16c56ad

> Fast-forward

> README.md | 5 +++--

> 1 file changed, 3 insertions(+), 2 deletions(-)

There, you’ve updated your fork!

«««< HEAD

3. Committing Code with Visual Tools

You’ve been able to learn the foundations of Git itself, but it may be difficult to remember individual commands, or exercise more control over what code you commit - thus, you may choose to use more visual tools to commit code.

A lot of modern IDEs will have some kind of integration with Git, such as IntelliJ or VSCode. However, there may be other

visual tools that you choose to use instead. For example, I used GitHub Desktop when

I first started out. There’s also the gitk command, which is provided with Git itself. If you run the command within a

folder hosting a repository, it’ll open up a window that looks like this:

gitk is only for viewing commits rather than making them, and is very verbose - so it may be better for reviewing the

finer details of commits in a GUI.

4. Submitting a Pull Request

As mentioned prior, you’ll often make a fork to contribute to the original work - and that’s where pull requests come in. They tend to have different names across different sites, since it’s not necessarily a Git feature - Gitlab calls them merge requests and Bit Bucket also calls them pull requests. Sometimes developers only address them as PRs as a shorthand, which I will do as well.

Once you’ve pushed your code, go to the main page of your fork, and check the “Contribute” button where it mentions your branch being ahead of your upstream repository:

Then, click the “Open pull request” button. GitHub will then prompt you for the title of the PR, a description of what the PR does, and the branches to merge into/from.

If you see the small dropdown arrow next to “Create pull request” too, you can create a pull request as a draft, meaning that you’ve not completed your work yet, but can accept early review from maintainers or other contributors.

Best Practices

When making pull requests, different projects will have different ideals or requirements - and it extends to more than just making a good title and description. Here’s a quick list of what you may find:

- Some repositories will not allow you to merge from your main branch.

- Ideally, it would come from a non-main branch where all of your work for that PR is focused.

- Some repositories may also not let you make a PR from a fork under an organisation.

- You may remember the “Allow edits and access to secrets by maintainers” option? It doesn’t apply to organisation forks. By consequence, project maintainers who want to edit your PRs to rebase or resolve nitpicks will ask for you to do them instead.

- PRs need a specific scope, e.g. if you intend on fixing a bug, it’s only that bug you fix, rather than some formatting changes too.

- In addition to the above, depending on what is covered, PRs would ideally not be too big. Otherwise, they become too

cumbersome for maintainers to review.

- They also increase the likelihood of complex merge conflicts that are a headache to resolve.

- Some repositories may require an issue to be opened before making a PR, which the PR then can link back to. This is often for maintainers to give their stance on the issue and what can be done next.

Merge Conflicts

After submitting your pull request, it’s likely that other PRs will be accepted and merged in, or the main codebase is changed over time. If those changes alter what your PR covers, that can result in merge conflicts, which maintainers may request for you to resolve in order for them to accept the PR. Some simple ones can be resolved within GitHub - however, more complex ones will have to be resolved locally.

Let’s not only take an example, but make a merge conflict. I have the guestbook, and it currently looks like this after switching to main:

git checkout main

---

layout: lecture

title: "Guestbook"

---

This guestbook was made for those participating in the "Git for Open Source Development" lecture in November 2024, to

demonstrate opening a pull request and contributing to an open-source project.

And I have a branch (add-holly-to-guestbook) to add myself:

git branch add-holly-to-guestbook

git checkout add-holly-to-guestbook

With the guestbook content being:

---

layout: lecture

title: "Guestbook"

---

This guestbook was made for those participating in the "Git for Open Source Development" lecture in November 2024, to

demonstrate opening a pull request and contributing to an open-source project.

- Holly, 4th Year MSci Computer Science

However, let’s say someone else makes some changes to the guestbook content, and it ends up in main:

---

layout: lecture

title: "Guestbook"

---

This guestbook was made for those participating in the "Git for Open Source Development" lecture in November 2024, to

demonstrate opening a pull request and contributing to an open-source project. Pls be nice

aaaaaa

a

a

Once I attempt to merge add-holly-to-guestbook into main:

git checkout add-holly-to-guestbook

git merge main

It results in something that looks like this:

Note: The conflicting branch here is

merge-conflict-test-2- in our example, this would bemain.HEADis also a stand-in foradd-holly-to-guestbook- it’s just a slight difference in how I produced the conflict.

This is a merge conflict. This may look scary at first, and there is reason behind the chaos it spits out - here’s the output we want to focus on:

<<<<<<< add-holly-to-guestbook

demonstrate opening a pull request and contributing to an open-source project.

- Holly, 4th Year MSci Computer Science

=======

demonstrate opening a pull request and contributing to an open-source project. Pls be nice

aaaaaa

a

a

>>>>>>> main

The conflict itself is encapsulated within the <<<<<<< and >>>>>>> arrows - but we may also choose to look outside of

this to gather further context about the conflict. Then, the two conflicting changes are separated by the equal signs

(=======). The first bit of code will often belong to the branch you’re currently in (add-holly-to-guestbook, or

when handling conflicts locally, HEAD), and the second bit will belong to the branch you’re trying to merge with (main).

There’s a few things you can do with this information:

- Ditch the bottom code (

main) and replace it with the code inadd-holly-to-guestbook.- For example, you may choose to do this if you’re working on a feature that makes the changes being conflicted with redundant.

- Do the opposite and ditch the top code (

add-holly-to-guestbook), replacing it with the code inmain.- You may also choose to do this when you’ve made changes that are no longer needed, e.g. a fix in a function that was deleted.

- Merge both changes together.

Let’s say that the screaming at the end was unnecessary, but the “Pls be nice” was an important part of the change made.

However, the whole point of the add-holly-to-guestbook branch was to add my name to the guestbook, so we want to keep

it. Ultimately, we just change the content to mix the both together:

<<<<<<< add-holly-to-guestbook

demonstrate opening a pull request and contributing to an open-source project. Pls be nice

- Holly, 4th Year MSci Computer Science

=======

demonstrate opening a pull request and contributing to an open-source project. Pls be nice

aaaaaa

a

a

>>>>>>> main

Then, you can remove the arrows and equal signs that a part of the conflict, including the old bit of the conflict that is now redundant:

demonstrate opening a pull request and contributing to an open-source project. Pls be nice

- Holly, 4th Year MSci Computer Science

From there, you can commit and push your changes. Git will allow you to push as long as all conflicts are resolved.

If you’re struggling with visualising conflicts and how to resolve them, IDEs will often try to help you along the way. For context, IntelliJ will often try to visualise merge conflicts by placing either content side by side, with your final changes in the middle, then letting you choose which part of the conflict you want to merge in with.

Code Reviews

After you’ve made a pull request, it will often be the case that maintainers will review it and suggest either code changes or make general comments.

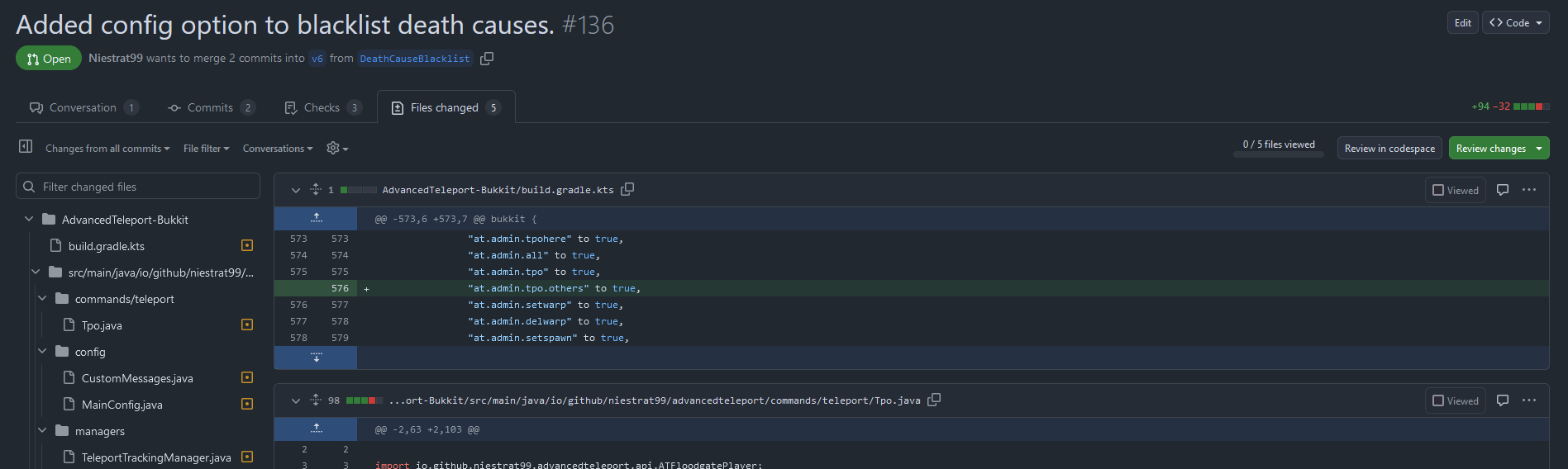

If you’re a maintainer, you may get prompted for a review on each PR made to your project. To add a review, just switch to the “Files changed” tab, then you can conduct a review:

As you go through each file, you can tick the “viewed” box to the right of the file, which will collapse it. If you need to make comments on certain lines, you can hover over the line numbers and click on the + icon that shows up, typing in your thoughts. You can either add it as a single comment or start a review - if you want the comment to be a part of the review, then use “Start a review”, and the comment will appear once you click “Review changes” at the top, at which point you can either approve the changes, comment on them without an explicit decision, or request changes.

When reviewing changes, it’s good to be constructive if changes are required - if there are formatting-specific issues, they should be verified as part of the CI/CD process.

5. Setting up a Repository for Contributions

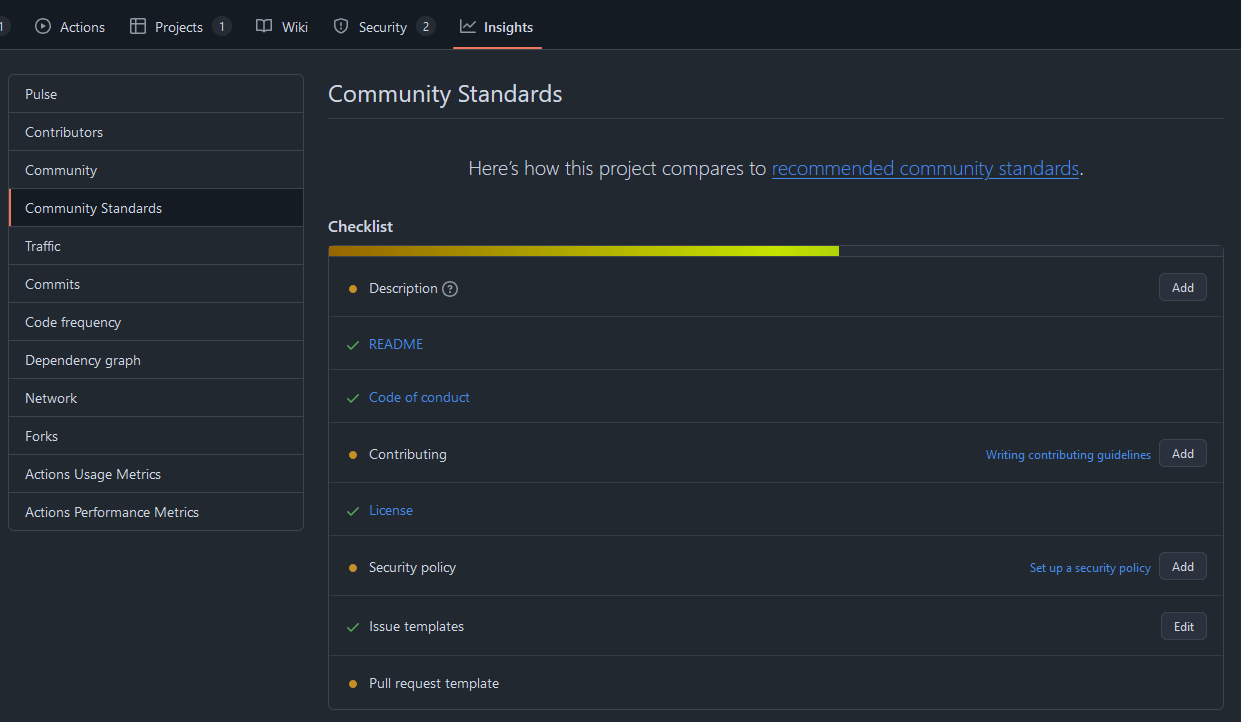

Now, let’s move onto the maintainer’s side of open source. GitHub has a community standards page in the Insights tab of your project, which you can treat as a todo list for setting up a project for open-source contributions. Not all of these are required for effective contribution, but some are vital, which I will go over below.

README

A README file is often the very first file that someone will see when visiting your repository. It will often give a quick overview of what the repository is, how to build/use it in development, and any other important links/bits of information that would be useful to know.

This file will often be called README or README.md.

Code of Conduct

A code of conduct is used as a set of rules how to treat other developers working on a project. It’s important to make sure everyone who participates in contributing to a project doesn’t feel ostracised or bullied. As per Open Source Guide’s guidance on code of conducts, It covers what is considered unacceptable behaviour, who it applies to, what happens when violations occur and how someone can report a violation.

GitHub will provide you with two default code of conducts if you’re not sure how to write you own, which are the Contributor Covenant (best for projects of all sorts of sizes), and the Citizen Code of Conduct (for large communities and events).

The code of conduct will often go into the root folder of your repository, called CODE_OF_CONDUCT.md.

License

A license is one of the most important components of your project, since it legally dictates what other developers can do with your work. There’s a lot of licenses to choose from, but copyleft licenses tend to be found the most, which require its derivative works (such as forks) to have the same rights as its own.

The three most common licenses that GitHub tend to push first are:

- Apache License 2.0 (this is what CSS’ website is under)

- GNU General Public License v3

- MIT License

To put these three into perspective, MIT allows you to create forks or derivatives under different terms and without publishing source code, GPLv3 requires derivatives to keep the same terms and have source code published, whilst the Apache License focuses on the preservation of copyright.

It’s highly important to stress that none of this is legal advice - if in doubt, seek advice from an actual lawyer. Before choosing a license too, I would highly recommend reading through each license to decide if it’s the license you want to use for your repository, and make your own choice.

The license will often go into the root folder of your repository, under the name LICENSE.

Security Policy

Security policies are important for when users need to report security vulnerabilities, but want to report them responsibly - thus, only you know about the vulnerability, and you’re given time to fix it. A security policy will often consist of the following:

- Versions supported for security updates

- How to report security vulnerabilities

The security policy will often go into the root folder of your repository, named as SECURITY.md.

Issue Templates and Forms

Issues can be immensely useful, but sometimes, you’ll need additional information from those who submit those issues - and sometimes, it will require the same information over and over, such as the version of the software being used, the device it is used on, etc. - you can use issue templates for that.

Issue templates can be written in markdown, which will then be used as a template for anyone filling out an issue. These

go into the .github/ISSUE_TEMPLATE folders, and suffixed with a .md, e.g. bug_report.md. GitHub also provides

examples for bugs and features.

However, issue templates can be deleted be users reporting bugs, much to developers’ demises - which is when issue forms

come in. These are a development in GitHub pretty much seen in every mainstream repository, enforcing you to fill out

certain fields and structure your report in a certain way. Instead of using .md files, issue forms are configured as

YAML /static/media/2024 (i.e. bug_report.yaml). These are a bit too complex for us to cover this lecture, but I’ve linked the

official documentation for creating an issue form

from GitHub’s documentation.

Pull Request Template

Like with issue templates, you may choose to have pull request templates that require developers to fill out certain information about their pull requests. However, unlike issue templates, these are far less common, presumably to be less cumbersome for contributors to make PRs. PR templates may request the issue number that is resolved by the PR, a summary or description of the PR, and tested environments.

Pull request templates go into the .github/PULL_REQUEST_TEMPLATE folders, and end with the .md suffix to signify

markdown.

Repository Admin Accepts Content Reports

This is a simple toggle option that allows repository maintainers or administrators to receive reports from users about content within the repository, and act on it accordingly. This is only particularly effective for larger projects, so this may not be of particular concern for smaller projects you have.

6. CI/CD and GitHub Actions

If you’re maintaining a repository, you’ll often find occasions where someone contributes code to your repository, you merge the changes in, just to find it completely breaks everything and the program no longer builds. Or even, another maintainer pushes directly to main, but it breaks everything for everyone else, even if it works on their machine. If you’re also building a website, you may want it to deploy automatically after each commit so that it’s always up to date. CI/CD can be used for all of this,

CI/CD stands for continuous integration and development. GitHub allows for this quite easily, and additionally provides pre-made workflows known as “Actions” for different checks or things you may want to do with your repository. For example, let’s say we want to test a Java project’s compilation.

For context, this is a personal repository that I am using as an example.

Let’s go into the Actions tab in the repository. When we go into the page, we’re greeted with workflows that are suggested

for the repository:

However, as we scroll, we also happen to find workflow categories, such as:

However, as we scroll, we also happen to find workflow categories, such as:

- Deployment

- Security

- Continuous Integration

- Automation

- Pages

Generally, each workflow will have a target language, so not all of them may work for you.

Because our Java project uses Gradle for its dependency management, let’s select the “Java with Gradle” workflow. When we select it, this is the file generated:

# This workflow uses actions that are not certified by GitHub.

# They are provided by a third-party and are governed by

# separate terms of service, privacy policy, and support

# documentation.

# This workflow will build a Java project with Gradle and cache/restore any dependencies to improve the workflow execution time

# For more information see: https://docs.github.com/en/actions/automating-builds-and-tests/building-and-testing-java-with-gradle

name: Java CI with Gradle

on:

push:

branches: [ "master" ]

pull_request:

branches: [ "master" ]

jobs:

build:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

permissions:

contents: read

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v4

- name: Set up JDK 17

uses: actions/setup-java@v4

with:

java-version: '17'

distribution: 'temurin'

# Configure Gradle for optimal use in GitHub Actions, including caching of downloaded dependencies.

# See: https://github.com/gradle/actions/blob/main/setup-gradle/README.md

- name: Setup Gradle

uses: gradle/actions/setup-gradle@af1da67850ed9a4cedd57bfd976089dd991e2582 # v4.0.0

- name: Build with Gradle Wrapper

run: ./gradlew build

# NOTE: The Gradle Wrapper is the default and recommended way to run Gradle (https://docs.gradle.org/current/userguide/gradle_wrapper.html).

# If your project does not have the Gradle Wrapper configured, you can use the following configuration to run Gradle with a specified version.

#

# - name: Setup Gradle

# uses: gradle/actions/setup-gradle@af1da67850ed9a4cedd57bfd976089dd991e2582 # v4.0.0

# with:

# gradle-version: '8.9'

#

# - name: Build with Gradle 8.9

# run: gradle build

dependency-submission:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

permissions:

contents: write

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v4

- name: Set up JDK 17

uses: actions/setup-java@v4

with:

java-version: '17'

distribution: 'temurin'

# Generates and submits a dependency graph, enabling Dependabot Alerts for all project dependencies.

# See: https://github.com/gradle/actions/blob/main/dependency-submission/README.md

- name: Generate and submit dependency graph

uses: gradle/actions/dependency-submission@af1da67850ed9a4cedd57bfd976089dd991e2582 # v4.0.0

Let’s go over this bit by bit:

- We have a name specified for the workflow, this being “Java CI with Gradle” - this name will come up when you check the Actions tab again.

- We’ve got the events for the workflow to be triggered listed, alongside the branches they should apply to. In this case, the workflow should attempt to build the repository whenever pushes are made to the master branch, or pull requests targeting the master branch are made.

- We’ve got two jobs, one running the build step, the other generating a dependency graph of the project.

- The build job has an environment configured, and requires permission to read the contents of the repository.

- It checkouts the repository locally first before setting up JDK 17 and Gradle.

- After that point, a build with the Gradle wrapper is attempted.

- A lot of the steps for the dependency graph are the same - however, instead of setting up Gradle, it cuts straight to the dependency graph.

There is a note in the workflow about using the Gradle wrapper - this is present in the repository, so we do not need the commented-out portion of the workflow.

=======

The conflict itself is encapsulated within the <<<<<<< and >>>>>>> arrows - but we may also choose to look outside of

this to gather further context about the conflict. Then, the two conflicting changes are separated by the equal signs

(=======). The first bit of code will often belong to the branch you’re currently in (add-holly-to-guestbook, or

when handling conflicts locally, HEAD), and the second bit will belong to the branch you’re trying to merge with (main).

There’s a few things you can do with this information:

- Ditch the bottom code (

main) and replace it with the code inadd-holly-to-guestbook.- For example, you may choose to do this if you’re working on a feature that makes the changes being conflicted with redundant.

- Do the opposite and ditch the top code (

add-holly-to-guestbook), replacing it with the code inmain.- You may also choose to do this when you’ve made changes that are no longer needed, e.g. a fix in a function that was deleted.

- Merge both changes together.

Let’s say that the screaming at the end was unnecessary, but the “Pls be nice” was an important part of the change made.

However, the whole point of the add-holly-to-guestbook branch was to add my name to the guestbook, so we want to keep

it. Ultimately, we just change the content to mix the both together:

<<<<<<< add-holly-to-guestbook

demonstrate opening a pull request and contributing to an open-source project. Pls be nice

- Holly, 4th Year MSci Computer Science

=======

demonstrate opening a pull request and contributing to an open-source project. Pls be nice

aaaaaa

a

a

>>>>>>> main

Then, you can remove the arrows and equal signs that a part of the conflict, including the old bit of the conflict that is now redundant:

demonstrate opening a pull request and contributing to an open-source project. Pls be nice

- Holly, 4th Year MSci Computer Science

From there, you can commit and push your changes. Git will allow you to push as long as all conflicts are resolved.

If you’re struggling with visualising conflicts and how to resolve them, IDEs will often try to help you along the way. For context, IntelliJ will often try to visualise merge conflicts by placing either content side by side, with your final changes in the middle, then letting you choose which part of the conflict you want to merge in with.

Code Reviews

After you’ve made a pull request, it will often be the case that maintainers will review it and suggest either code changes or make general comments.

If you’re a maintainer, you may get prompted for a review on each PR made to your project. To add a review, just switch to the “Files changed” tab, then you can conduct a review:

As you go through each file, you can tick the “viewed” box to the right of the file, which will collapse it. If you need to make comments on certain lines, you can hover over the line numbers and click on the + icon that shows up, typing in your thoughts. You can either add it as a single comment or start a review - if you want the comment to be a part of the review, then use “Start a review”, and the comment will appear once you click “Review changes” at the top, at which point you can either approve the changes, comment on them without an explicit decision, or request changes.

When reviewing changes, it’s good to be constructive if changes are required - if there are formatting-specific issues, they should be verified as part of the CI/CD process.

5. Setting up a Repository for Contributions

Now, let’s move onto the maintainer’s side of open source. GitHub has a community standards page in the Insights tab of your project, which you can treat as a todo list for setting up a project for open-source contributions. Not all of these are required for effective contribution, but some are vital, which I will go over below.

README

A README file is often the very first file that someone will see when visiting your repository. It will often give a quick overview of what the repository is, how to build/use it in development, and any other important links/bits of information that would be useful to know.

This file will often be called README or README.md.

Code of Conduct

A code of conduct is used as a set of rules how to treat other developers working on a project. It’s important to make sure everyone who participates in contributing to a project doesn’t feel ostracised or bullied. As per Open Source Guide’s guidance on code of conducts, It covers what is considered unacceptable behaviour, who it applies to, what happens when violations occur and how someone can report a violation.

GitHub will provide you with two default code of conducts if you’re not sure how to write you own, which are the Contributor Covenant (best for projects of all sorts of sizes), and the Citizen Code of Conduct (for large communities and events).

The code of conduct will often go into the root folder of your repository, called CODE_OF_CONDUCT.md.

License

A license is one of the most important components of your project, since it legally dictates what other developers can do with your work. There’s a lot of licenses to choose from, but copyleft licenses tend to be found the most, which require its derivative works (such as forks) to have the same rights as its own.

The three most common licenses that GitHub tend to push first are:

- Apache License 2.0 (this is what CSS’ website is under)

- GNU General Public License v3

- MIT License

To put these three into perspective, MIT allows you to create forks or derivatives under different terms and without publishing source code, GPLv3 requires derivatives to keep the same terms and have source code published, whilst the Apache License focuses on the preservation of copyright.

It’s highly important to stress that none of this is legal advice - if in doubt, seek advice from an actual lawyer. Before choosing a license too, I would highly recommend reading through each license to decide if it’s the license you want to use for your repository, and make your own choice.

The license will often go into the root folder of your repository, under the name LICENSE.

Security Policy

Security policies are important for when users need to report security vulnerabilities, but want to report them responsibly - thus, only you know about the vulnerability, and you’re given time to fix it. A security policy will often consist of the following:

- Versions supported for security updates

- How to report security vulnerabilities

The security policy will often go into the root folder of your repository, named as SECURITY.md.

Issue Templates and Forms

Issues can be immensely useful, but sometimes, you’ll need additional information from those who submit those issues - and sometimes, it will require the same information over and over, such as the version of the software being used, the device it is used on, etc. - you can use issue templates for that.

Issue templates can be written in markdown, which will then be used as a template for anyone filling out an issue. These

go into the .github/ISSUE_TEMPLATE folders, and suffixed with a .md, e.g. bug_report.md. GitHub also provides

examples for bugs and features.

However, issue templates can be deleted be users reporting bugs, much to developers’ demises - which is when issue forms

come in. These are a development in GitHub pretty much seen in every mainstream repository, enforcing you to fill out

certain fields and structure your report in a certain way. Instead of using .md files, issue forms are configured as

YAML files (i.e. bug_report.yaml). These are a bit too complex for us to cover this lecture, but I’ve linked the

official documentation for creating an issue form

from GitHub’s documentation.

Pull Request Template

Like with issue templates, you may choose to have pull request templates that require developers to fill out certain information about their pull requests. However, unlike issue templates, these are far less common, presumably to be less cumbersome for contributors to make PRs. PR templates may request the issue number that is resolved by the PR, a summary or description of the PR, and tested environments.

Pull request templates go into the .github/PULL_REQUEST_TEMPLATE folders, and end with the .md suffix to signify

markdown.

Repository Admin Accepts Content Reports

This is a simple toggle option that allows repository maintainers or administrators to receive reports from users about content within the repository, and act on it accordingly. This is only particularly effective for larger projects, so this may not be of particular concern for smaller projects you have.

6. CI/CD and GitHub Actions

If you’re maintaining a repository, you’ll often find occasions where someone contributes code to your repository, you merge the changes in, just to find it completely breaks everything and the program no longer builds. Or even, another maintainer pushes directly to main, but it breaks everything for everyone else, even if it works on their machine. If you’re also building a website, you may want it to deploy automatically after each commit so that it’s always up to date. CI/CD can be used for all of this,

CI/CD stands for continuous integration and development. GitHub allows for this quite easily, and additionally provides pre-made workflows known as “Actions” for different checks or things you may want to do with your repository. For example, let’s say we want to test a Java project’s compilation.

For context, this is a personal repository that I am using as an example.

Let’s go into the Actions tab in the repository. When we go into the page, we’re greeted with workflows that are suggested

for the repository:

However, as we scroll, we also happen to find workflow categories, such as:

However, as we scroll, we also happen to find workflow categories, such as:

- Deployment

- Security

- Continuous Integration

- Automation

- Pages

Generally, each workflow will have a target language, so not all of them may work for you.

Because our Java project uses Gradle for its dependency management, let’s select the “Java with Gradle” workflow. When we select it, this is the file generated:

# This workflow uses actions that are not certified by GitHub.

# They are provided by a third-party and are governed by

# separate terms of service, privacy policy, and support

# documentation.

# This workflow will build a Java project with Gradle and cache/restore any dependencies to improve the workflow execution time

# For more information see: https://docs.github.com/en/actions/automating-builds-and-tests/building-and-testing-java-with-gradle

name: Java CI with Gradle

on:

push:

branches: [ "master" ]

pull_request:

branches: [ "master" ]

jobs:

build:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

permissions:

contents: read

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v4

- name: Set up JDK 17

uses: actions/setup-java@v4

with:

java-version: '17'

distribution: 'temurin'

# Configure Gradle for optimal use in GitHub Actions, including caching of downloaded dependencies.

# See: https://github.com/gradle/actions/blob/main/setup-gradle/README.md

- name: Setup Gradle

uses: gradle/actions/setup-gradle@af1da67850ed9a4cedd57bfd976089dd991e2582 # v4.0.0

- name: Build with Gradle Wrapper

run: ./gradlew build

# NOTE: The Gradle Wrapper is the default and recommended way to run Gradle (https://docs.gradle.org/current/userguide/gradle_wrapper.html).

# If your project does not have the Gradle Wrapper configured, you can use the following configuration to run Gradle with a specified version.

#

# - name: Setup Gradle

# uses: gradle/actions/setup-gradle@af1da67850ed9a4cedd57bfd976089dd991e2582 # v4.0.0

# with:

# gradle-version: '8.9'

#

# - name: Build with Gradle 8.9

# run: gradle build

dependency-submission:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

permissions:

contents: write

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v4

- name: Set up JDK 17

uses: actions/setup-java@v4

with:

java-version: '17'

distribution: 'temurin'

# Generates and submits a dependency graph, enabling Dependabot Alerts for all project dependencies.

# See: https://github.com/gradle/actions/blob/main/dependency-submission/README.md

- name: Generate and submit dependency graph

uses: gradle/actions/dependency-submission@af1da67850ed9a4cedd57bfd976089dd991e2582 # v4.0.0

Let’s go over this bit by bit:

- We have a name specified for the workflow, this being “Java CI with Gradle” - this name will come up when you check the Actions tab again.

- We’ve got the events for the workflow to be triggered listed, alongside the branches they should apply to. In this case, the workflow should attempt to build the repository whenever pushes are made to the master branch, or pull requests targeting the master branch are made.

- We’ve got two jobs, one running the build step, the other generating a dependency graph of the project.

- The build job has an environment configured, and requires permission to read the contents of the repository.

- It checkouts the repository locally first before setting up JDK 17 and Gradle.

- After that point, a build with the Gradle wrapper is attempted.

- A lot of the steps for the dependency graph are the same - however, instead of setting up Gradle, it cuts straight to the dependency graph.

There is a note in the workflow about using the Gradle wrapper - this is present in the repository, so we do not need the commented-out portion of the workflow.

upstream/master However, if we want to test with multiple versions of Java, we can set up a matrix of versions to test against: ```yaml jobs: build: name: Build on $ runs-on: ubuntu-latest permissions: contents: read strategy: matrix: java-version: [‘17’, ‘21’]

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v4

- name: Set up JDK $

uses: actions/setup-java@v4

with:

java-version: $

distribution: 'temurin' ``` From there, the workflow will loop through each version and run the job with each one. You can then use the matrix placeholder to represent each run.

You can also choose to run different jobs or steps depending on certain outcomes. For example, let’s say we only want our dependency graph job to run if the build job succeeded:

jobs:

# ...

dependency-submission:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

permissions:

contents: write

if: jobs.build.result == 'success'

GitHub has a full list of contexts that can be used in conditional statements here.

Once you commit a workflow file, it will have to be on the main branch in order to run - workflow files in an alternative branch will not run, including in PRs.

You can read more about GitHub Actions here.

7. Alternatives to GitHub

There are plenty of alternatives to GitHub itself, and there may be several reasons why you choose to not host your code on GitHub. On some occasions it’s down to preference, but there is also a movement to give up GitHub entirely due to concerns about Copilot being trained on GitHub projects without developers’ consent, ties to the ICE in the USA, and the site itself being proprietary software that people have to rely on rather than being able to choose for themselves.

Although still proprietary, some alternatives you may have heard of include:

You can also self-host your Git hosts:

- Gitlab Community Edition - this one isn’t proprietary.

- Gitea

8. Final Thoughts

There’s numerous features part of sites like GitHub and Gitlab that make contributing to open source projects far easier and more streamlined. However, there’s still plenty of things I haven’t gone over - feel free to explore them in your own time:

- Documentation for software, either using GitHub’s wiki feature, Gitbook and many others.

- Adding maintainers to a repository, or requiring code reviewers through the CODEOWNERS file.

Licensed under CC BY-NC-SA.