#4: Shell Advanced

While the UoB version of this session will cover the same base material, please expect some differences during the live session.

Using the Shell

Globbing

There are often cases when you want to operate over multiple files. You could specify them individually, but bash has ways of making this easier, expanding expressions by carrying out filename expansion. These techniques are often referred to as shell globbing.

- Wildcards - Whenever you want to perform some sort of wildcard matching, you can use

?and*to match one or any amount of characters respectively. For instance, with these files, the commandrm foo?will deletefoo1andfoo2whereasrm foo*will delete all but bar.

$ ls

bar foo foo1 foo10 foo2

$ rm foo?

$ ls

bar foo foo10

- Curly braces

{}- Whenever you have a common substring in a series of commands, you can use curly braces for bash to expand this automatically. This comes in very handy when moving or converting files.

convert image.{png,jpg}

# Will expand to

convert image.png image.jpg

cp project/{foo,bar,baz}.sh new-project

# Will expand to

cp project/foo.sh project/bar.sh project/baz.sh new-project

# Globbing techniques can also be combined

mv *.{py,sh} new-project

# Will move all *.py and *.sh files

mkdir foo bar

# This creates files foo/a, foo/b, ... foo/h, bar/a, bar/b, ... bar/h

touch {foo,bar}/{a..h}

touch foo/x bar/y

History

So far we have seen how to find files and code, but as you start spending more time in the shell, you may want to find specific commands you typed at some point. The first thing to know is that typing the up arrow will give you back your last command, and if you keep pressing it you will slowly go through your shell history.

The history command will let you access your shell history programmatically. It will print your shell history to the standard output. If we want to search there we can pipe that output to grep and search for patterns. history | grep find will print commands that contain the substring “find”.

In most shells, you can make use of Ctrl+R to perform backwards search through your history. After pressing Ctrl+R, you can type a substring you want to match for commands in your history. As you keep pressing it, you will cycle through the matches in your history.

You can modify your shell’s history behavior, like preventing commands with a leading space from being included. This comes in handy when you are typing commands with passwords or other bits of sensitive information. To do this, add HISTCONTROL=ignorespace to your .bashrc. If you make the mistake of not adding the leading space, you can always manually remove the entry by editing your .bash_history.

Aliases

It can become tiresome typing long commands that involve many flags or verbose options. For this reason, most shells support aliasing. A shell alias is a short form for another command that your shell will replace automatically for you. For instance, an alias in bash has the following structure:

alias alias_name="command_to_alias arg1 arg2"

Note that there is no space around the equal sign =, because alias is a shell command that takes a single argument.

# Make shorthands for common flags

alias ll="ls -lh"

# Save a lot of typing for common commands

alias gs="git status"

alias gc="git commit"

alias v="vim"

# Save you from mistyping

alias sl=ls

# Overwrite existing commands for better defaults

alias mv="mv -i" # -i prompts before overwrite

alias mkdir="mkdir -p" # -p make parent dirs as needed

alias df="df -h" # -h prints human readable format

# Alias can be composed

alias la="ls -A"

alias lla="la -l"

# To ignore an alias run it prepended with \

\ls

# Or disable an alias altogether with unalias

unalias la

# To get an alias definition just call it with alias

alias ll

# Will print ll='ls -lh'

Common Shortcuts

We won’t cover all of the available keyboard shortcuts in bash; additionally, it is unlikely that you will be able to remember them all! As such, you should consult the bash manual page (man bash) for a comprehensive list. Despite that, here are some of the most useful ones:

| Shortcut | Action |

|---|---|

| Tab | Attempt to auto-complete |

| Ctrl-a | Move to start of line |

| Ctrl-e | Move to end of line |

| Alt-f | Move forward one word |

| Alt-b | Move backward one word |

| Ctrl-l | Clear screen |

| Ctrl-r | Recall from command history |

| Alt-< | Move to start of history |

| Alt-> | Move to end of history |

| Ctrl-k | Kill (cut) to end of line |

You might recognise some of these shortcuts as being quite similar to those available in Emacs. Worry not if you prefer Vim keybindings: bash supports Vim emulation - add set -o vi to your .bashrc.

Return Codes & stderr

As you know, commands will often send output to stdout, which is either displayed or plumbed through a pipe to another command. Commands can also send output to stderr - often printed to the display, although this can also be redirected somewhere else. More interestingly, commands also have a “return code” or “exit code”. The return code or exit status is the way commands have to communicate how execution went. A value of 0 usually means everything went OK; anything different from 0 means an error occurred. It’s possible to see the exit code of the last command with echo $?:

Exit codes can be used to conditionally execute commands using && (and operator) and || (or operator), both of which are short-circuiting operators. Commands can also be separated within the same line using a semicolon ;. The true program will always have a 0 return code and the false command will always have a 1 return code. Let’s see some examples:

false || echo "Oops, fail"

# Oops, fail

true || echo "Will not be printed"

#

true && echo "Things went well"

# Things went well

false && echo "Will not be printed"

#

true ; echo "This will always run"

# This will always run

false ; echo "This will always run"

# This will always run

true; echo $?

# 0

false; echo $?

# 1

Command & Variable Substitution

Sometimes it’s useful to have the output of one command be part of another. This can be done with command substitution. Whenever you place $( CMD ) it will execute CMD, get the output of the command and substitute it in place. A lesser known similar feature is process substitution, <( CMD ) will execute CMD and place the output in a temporary file and substitute the <() with that file’s name. This is useful when commands expect values to be passed by file instead of by STDIN.

Additionally, any defined variables - such as environment variables - can also be substituted in with the syntax $MY_VARIABLE.

That was a lot of info, so let’s give some examples:

echo "The date today is $(date)!"

echo "I'm running $SHELL!"

# find the details of every file newer than a certain date

ls -la $(find . -newer FILE)

# determine if an executable is native or a shell script

file $(which command)

# determine the true location of an executable by following symlinks

realpath $(which command)

Additionally, these substitutions are valid within "" delimiters but will not be expanded within '' delimiters. As you can see above, they will be expanded outside of these delimiters too.

Shells & Frameworks

Up till now we have been using the bash shell. bash, which stands for the ‘Bourne Again SHell’, is one of many commonly used Unix shells. Linux is a sort of Unix-like OS, and Unix shells provide the command-line interface for Unix-style operating systems. However, from now on we’ll just say shells when talking about Unix shells for the sake of brevity.

We’ve been working with bash so far because it is by far the most ubiquitous shell and most systems have it as the default option. Nevertheless, it is not the only option.

For example, the zsh shell is a superset of bash and provides many convenient features out of the box such as:

- Smarter globbing,

** - Inline globbing/wildcard expansion

- Spelling correction

- Better tab completion/selection

- Path expansion (

cd /u/lo/bwill expand as/usr/local/bin)

Some of the above features may also be available in bash, but may need you to actively enable them.

Frameworks can improve your shell as well. Some popular general frameworks are prezto or oh-my-zsh, and smaller ones that focus on specific features such as zsh-syntax-highlighting or zsh-history-substring-search. Shells like fish include many of these user-friendly features by default. Some of these features include:

- Right prompt

- Command syntax highlighting

- History substring search

- manpage based flag completions

- Smarter autocompletion

- Prompt themes

One thing to note when using these frameworks is that they may slow down your shell, especially if the code they run is not properly optimized or it is too much code. You can always profile it and disable the features that you do not use often or value over speed.

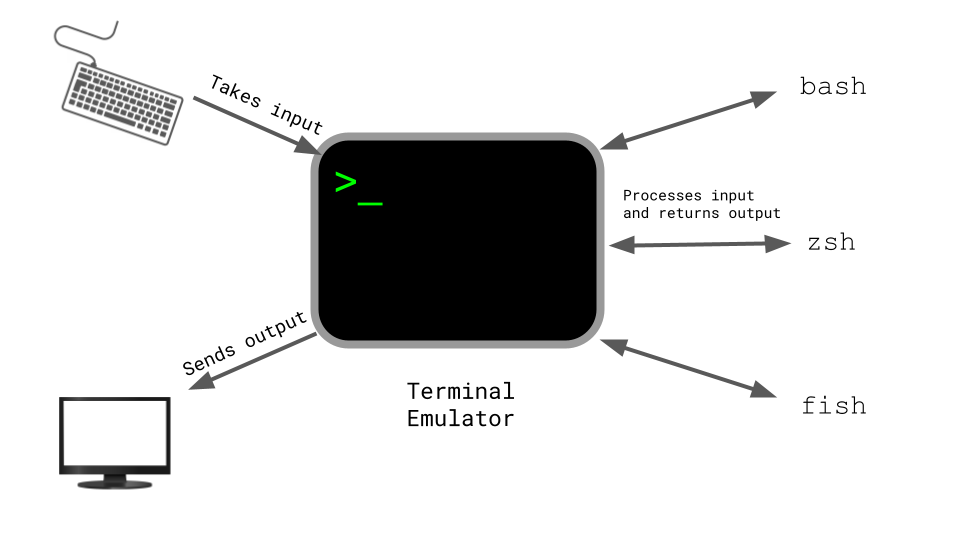

Terminal Emulators

Along with customizing your shell, it is worth spending some time figuring out your choice of terminal emulator and its settings. There are many many terminal emulators out there (here is a comparison).

Terminal emulators are the graphical program that your shell runs in. They mange input (eg. from a keyboard) and output (eg. your display) and communicate with the running shell. The shell takes this input, processes it, and tells the terminal what to output. The name is a legacy term back when ‘terminals’ were a piece of hardware separate from your computer mainframe. Now technology has come far enough that you can run multiple terminal programs on your computer, which is why they’re called terminal emulators!

Since you might be spending hundreds to thousands of hours in your terminal it pays off to look into its settings. Some of the aspects that you may want to modify in your terminal include:

- Font choice

- Color Scheme

- Keyboard shortcuts

- Tab/Pane support

- Scrollback configuration

- Performance (some newer terminals like Alacritty or kitty offer GPU acceleration).

Job Control and Multiplexing

Job Control

In some cases you will need to interrupt a job while it is executing, for instance if a command is taking too long to complete (such as a find with a very large directory structure to search through). Most of the time, you can do Ctrl-C and the command will stop. But how does this actually work, and why does it sometimes fail to stop the process?

Killing Processes

Your shell is using a UNIX communication mechanism called a signal to communicate information to the process. When a process receives a signal it stops its execution, deals with the signal and potentially changes the flow of execution based on the information that the signal delivered. For this reason, signals are software interrupts.

In our case, when typing Ctrl-C this prompts the shell to deliver a SIGINT signal to the process. By default, SIGINT will cause a process to exit. However, as with many other signals, processes can handle SIGINT in whatever way they please, including ignoring it. SIGINT is one of many UNIX signals; for example, by typing Ctrl-\, we can instead send the SIGQUIT signal.

Here’s an example of a small program that captures SIGINT and ignores it. To kill this program it is instead necessary to send the SIGQUIT signal.

#!/usr/bin/env python

import signal, time

def handler(signum, time):

print("\nI got a SIGINT, but I am not stopping")

signal.signal(signal.SIGINT, handler)

i = 0

while True:

time.sleep(.1)

print("\r{}".format(i), end="")

i += 1

And here’s what it looks like when we try to send SIGINT twice followed by SIGQUIT:

$ python sigint.py

24^C

I got a SIGINT, but I am not stopping

26^C

I got a SIGINT, but I am not stopping

30^\[1] 39913 quit python sigint.py

While SIGINT and SIGQUIT are both usually associated with terminal related requests, a more generic signal for asking a process to exit gracefully is the SIGTERM signal. To send this signal we can use the kill command, with the syntax kill -TERM <PID>. Should a process refuse to stop, you send the SIGKILL signal with kill -KILL <PID>. SIGKILL cannot be handled or intercepted by a process and instructs the kernel to kill it without giving it a change to respond.

Pausing and Backgrounding Processes

Signals can do other things beyond killing a process. For instance, SIGSTOP pauses a process. In the terminal, typing Ctrl-Z will prompt the shell to send a SIGTSTP signal, short for Terminal Stop (i.e. the terminal’s version of SIGSTOP).

We can then continue the paused job in the foreground or in the background using fg or bg, respectively.

The jobs command lists the unfinished jobs associated with the current terminal session. You can refer to those jobs using their PID (you can use pgrep or ps to find that out). More intuitively, you can also refer to a process using the percent symbol followed by its job number (displayed by jobs). To refer to the last backgrounded job you can use the $! special parameter.

One more thing to know is that the & suffix in a command will run the command in the background, giving you the prompt back, although it will still use the shell’s STDOUT which can be annoying (use shell redirections in that case).

To background an already running program you can do Ctrl-Z followed by bg. Note that backgrounded processes are still children processes of your terminal and will die if you close the terminal (this will send yet another signal, SIGHUP). To prevent that from happening you can use disown if the process has already been started. Alternatively, you can use a terminal multiplexer as we will see in the next section.

Below is a sample session to showcase some of these concepts.

$ sleep 1000

^Z

[1] + 18653 suspended sleep 1000

$ nohup sleep 2000 &

[2] 18745

appending output to nohup.out

$ jobs

[1] + suspended sleep 1000

[2] - running nohup sleep 2000

$ bg %1

[1] - 18653 continued sleep 1000

$ jobs

[1] - running sleep 1000

[2] + running nohup sleep 2000

$ kill -STOP %1

[1] + 18653 suspended (signal) sleep 1000

$ jobs

[1] + suspended (signal) sleep 1000

[2] - running nohup sleep 2000

$ kill -SIGHUP %1

[1] + 18653 hangup sleep 1000

$ jobs

[2] + running nohup sleep 2000

$ kill -SIGHUP %2

$ jobs

[2] + running nohup sleep 2000

$ kill %2

[2] + 18745 terminated nohup sleep 2000

$ jobs

You can learn more about these and other signals here or typing man signal or kill -l.

Terminal Multiplexing

When using the command line interface you will often want to run more than one thing at once. For instance, you might want to run your editor and your program side by side. Although this can be achieved by opening new terminal windows, using a terminal multiplexer is a more versatile solution.

Terminal multiplexers like tmux allow you to multiplex terminal windows using panes and tabs so you can interact with multiple shell sessions. Moreover, terminal multiplexers let you detach a current terminal session and reattach at some point later in time.

The most popular terminal multiplexer these days is tmux. tmux is highly configurable and by using the associated keybindings you can create multiple tabs and panes and quickly navigate through them.

tmux expects you to know its keybindings, and they all have the form <C-b> x where that means (1) press Ctrl+b, (2) release Ctrl+b, and then (3) press x. tmux has the following hierarchy of objects:

- Sessions - a session is an independent workspace with one or more windows

tmuxstarts a new session.tmux new -s NAMEstarts it with that name.tmux lslists the current sessions- Within

tmuxtyping<C-b> ddetaches the current session tmux aattaches the last session. You can use-tflag to specify which

- Windows - Equivalent to tabs in editors or browsers, they are visually separate parts of the same session

<C-b> cCreates a new window. To close it you can just terminate the shells doing<C-d><C-b> NGo to the N th window. Note they are numbered<C-b> pGoes to the previous window<C-b> nGoes to the next window<C-b> ,Rename the current window<C-b> wList current windows

- Panes - Like vim splits, panes let you have multiple shells in the same visual display.

<C-b> "Split the current pane horizontally<C-b> %Split the current pane vertically<C-b> <direction>Move to the pane in the specified direction. Direction here means arrow keys.<C-b> zToggle zoom for the current pane<C-b> [Start scrollback. You can then press<space>to start a selection and<enter>to copy that selection.<C-b> <space>Cycle through pane arrangements.

Terminal multiplexers can also be particularly useful when doing remote work, as you can then have both your local and your remote work session viewable in the same tmux session. Some terminals (such as iTerm2) will have some terminal multiplexing functionality built-in, so it is up to you to decide if you would rather use that.

SSH

Executing commands

An often overlooked feature of ssh is the ability to run commands directly.

ssh foobar@server ls will execute ls in the home folder of foobar.

It works with pipes, so ssh foobar@server ls | grep PATTERN will grep locally the remote output of ls and ls | ssh foobar@server grep PATTERN will grep remotely the local output of ls.

SSH Config

If you connect to a remote host often, it might be frustrating to keep telling ssh the connection details. For this reason ssh supports being configured via the ~/.ssh/config file. Each entry in this file represents a known host. For example, for some server foo you might have an entry such as:

HOST foo

User my_username

HostName foo.example.com

Port 2222

This would allow you to connect to this host by typing ssh foo rather than ssh my_username@foo.example.com -p 2222. As well as giving common hosts short and convenient names, it is also possible to specify additional options - such as forcing a specific command to be executed on connection by default, such as your favourite shell. These names can also be used with other tools that use SSH, such as scp - more on that later.

Key Management

Key-based authentication exploits public-key cryptography to prove to the server that the client owns the secret private key without revealing the key. This way you do not need to reenter your password every time. Nevertheless, the private key (often ~/.ssh/id_rsa and more recently ~/.ssh/id_ed25519) is effectively your password, so treat it like so.

Key generation

To generate a pair you can run ssh-keygen.

ssh-keygen -o -a 100 -t ed25519 -f ~/.ssh/id_ed25519

You should choose a passphrase, to avoid someone who gets hold of your private key to access authorized servers. Use ssh-agent or gpg-agent so you do not have to type your passphrase every time.

Key based authentication

ssh will look into .ssh/authorized_keys to determine which clients it should let in. To copy a public key over you can use:

cat .ssh/id_ed25519.pub | ssh foobar@remote 'cat >> ~/.ssh/authorized_keys'

A simpler solution can be achieved with ssh-copy-id where available:

ssh-copy-id -i .ssh/id_ed25519 foobar@remote

Copying files over SSH

There are many ways to copy files over ssh, of which the most straightforward is scp. The syntax is scp path/to/local_file remote_host:path/to/remote_file. For are more powerful tool - for example if you are copying a large amount of data - consider rsync. It has the ability to stop and resume copies and has fine-grained control when handling permissions and symlinks.

Dotfiles

Many programs are configured using plain-text files known as dotfiles

(because the file names begin with a ., e.g. ~/.vimrc, so that they are

hidden in the directory listing ls by default).

Shells are one example of programs configured with such files. On startup, your shell will read many files to load its configuration. Depending on the shell, whether you are starting a login and/or interactive the entire process can be quite complex. Here is an excellent resource on the topic.

For bash, editing your .bashrc or .bash_profile will work in most systems.

Here you can include commands that you want to run on startup, like the alias we just described or modifications to your PATH environment variable.

In fact, many programs will ask you to include a line like export PATH="$PATH:/path/to/program/bin" in your shell configuration file so their binaries can be found.

Some other examples of tools that can be configured through dotfiles are:

bash-~/.bashrc,~/.bash_profilegit-~/.gitconfigvim-~/.vimrcand the~/.vimfolderssh-~/.ssh/configtmux-~/.tmux.conf

You also often encounter .profile files, which contain shell-independent shell configuration options such as environment variables. If .profile is used, it’s good practice to avoid having shell-specific commands in .profile to avoid compatibility issues further down the line.

How should you organize your dotfiles? They should be in their own folder, under version control, and symlinked into place using a script. This has the benefits of:

- Easy installation: if you log in to a new machine, applying your customizations will only take a minute.

- Portability: your tools will work the same way everywhere.

- Synchronization: you can update your dotfiles anywhere and keep them all in sync.

- Change tracking: you’re probably going to be maintaining your dotfiles for your entire programming career, and version history is nice to have for long-lived projects.

What should you put in your dotfiles? You can learn about your tool’s settings by reading online documentation or man pages. Another great way is to search the internet for blog posts about specific programs, where authors will tell you about their preferred customizations. Yet another way to learn about customizations is to look through other people’s dotfiles: you can find tons of dotfiles repositories on Github — see the most popular one here (we advise you not to blindly copy configurations though). Here is another good resource on the topic.

All of the class instructors have their dotfiles publicly accessible on GitHub: Anish, Jon, Jose.

Portability

A common pain with dotfiles is that the configurations might not work when working with several machines, e.g. if they have different operating systems or shells. Sometimes you also want some configuration to be applied only in a given machine.

There are some tricks for making this easier. If the configuration file supports it, use the equivalent of if-statements to apply machine specific customizations. For example, your shell could have something like:

if [[ "$(uname)" == "Linux" ]]; then {do_something}; fi

# Check before using shell-specific features

if [[ "$SHELL" == "zsh" ]]; then {do_something}; fi

# You can also make it machine-specific

if [[ "$(hostname)" == "myServer" ]]; then {do_something}; fi

If the configuration file supports it, make use of includes. For example,

a ~/.gitconfig can have a setting:

[include]

path = ~/.gitconfig_local

And then on each machine, ~/.gitconfig_local can contain machine-specific

settings. You could even track these in a separate repository for

machine-specific settings.

This idea is also useful if you want different programs to share some configurations. For instance, if you want both bash and zsh to share the same set of aliases you can write them under .aliases and have the following block in both:

# Test if ~/.aliases exists and source it

if [ -f ~/.aliases ]; then

source ~/.aliases

fi

Regex

Introduction

Regular expressions are common and useful enough that it’s worthwhile to take some time to understand how they work. They are a tool for matching text - for example, you might want to match certain lines in a file or specify a pattern to replace in a file. By using regular expressions - or “regexps” - we can describe sophisticated patterns for matching text.

Most characters just carry their normal meaning - for example, the regex “example” matches the literal string “example”, but some characters have “special” matching behavior. Exactly which characters do what vary somewhat between different implementations of regular expressions, which is a source of great frustration. Very common patterns are:

.means “any single character” except newline*zero or more of the preceding match+one or more of the preceding match[abc]any one character ofa,b, andc(RX1|RX2)either something that matchesRX1orRX2^the start of the line$the end of the line\w \d \smatch words, digits, or whitespace

For example, the regexp [b-d]\s* would match any character in the range of b to d (so b, c, and d), followed by zero or more whitespace characters. Below is an excerpt from Alice in Wonderland where all the matching patterns have been surrounded with square brackets:

Ali[c]e was [b]eginning to get very tire[d ]of sitting [b]y her sister on the [b]ank, an[d ]of having nothing to [d]o: on[c]e or twi[c]e she ha[d ]peepe[d] into the [b]ook her sister was rea[d]ing, [b]ut it ha[d] no pi[c]tures or [c]onversations in it, “an[d ]what is the use of a [b]ook,” thought Ali[c]e “without pi[c]tures or [c]onversations?”

With these patterns it becomes possible to specify sophisticated patterns for matching strings. Some patterns that you may find useful would be:

\d{1,3}\.\d{1,3}\.\d{1,3}\.\d{1,3}matches IPv4 Addresses.+\@.+\..+is a simple email address regexp pattern[0-9]{1,2}\/[0-9]{1,2}\/[0-9]{4}is a pattern matching dates in the format dd/mm/yyyy (note that this would match invalid dates like 60/24/7800 as well!)

Tools

Regular expressions are powerful, but it can often be difficult to construct them or understand why one isn’t matching text that you expect it should. For that reason it might be valuable to use tools that can help you build and debug regular expressions, such as this one.

grep

grep is a tool for matching text using regular expressions. You’ve seen grep briefly before for filtering out lines of text, but now that we understand regular expressions we can use grep to perform powerful filtering:

history | grep -P "cat .*\.txt"'will search through your shell history for lines where you havecat-ed any file ending in.txtip a | grep -P "\d{1,3}\.\d{1,3}\.\d{1,3}\.\d{1,3}"takes the output of the commandip aand return the lines that have an IPv4 address in them

Using grep to search through your filesystem and the contents of files can be incredibly powerful!

sed

sed, the “stream editor”, is a tool for modifying text. It accepts some stream of text - such as a file on disk or some input that you have piped into it - and applies some modification to it. sed can do many things, but it is commonly used for text substitution with the s command. The s command is written in the form: s/REGEX/SUBSTITUTION/, where REGEX is the regular expression you want to search for, and SUBSTITUTION is the text you want to substitute matching text with. Say - for example - that you have this file and realize that you would like to replace every occurrence of “Alice” with “Bob”. You could use sed, passing the -i flag (replace in-place), like this:

sed -i 's/Alice/Bob/g' s-example.txt

Here the final g means “global”, which is sed-speak for “replace every occurrence, not just the first on each line”. Of course this is a simple example, and sed can match with the full power of regular expressions. sed regular expressions are somewhat weird, and will require you to put a \ before most of these to give them their special meaning. Or you can pass the -E flag.

A Spot of Scripting

So far we have been using the shell in an interactive way, where we write one command and see the results returned to us. You may have also noticed two things about the shell: its syntax can be quite unusual, and that it is possible to express powerful behaviour in very few commands. With this in mind we can look at shell scripting, which allows us to write shell commands into a file to be run later. As well as running a series of commands in order, just as you might, it is possible to use various control flow expressions you might be familiar with - such as loops or conditional expressions - to decide which commands to run.

A Basic Example

The most basic use case for a shell script is that you have one or more commands that you often run that you would like to remember. Such a script might look like this:

#!/usr/bin/env bash

my_first_command

my_second_command

Note that it starts with the line #!/usr/bin/env bash. When this script is run, this line tells Linux to use bash to execute this script.

Variables

As you are now familiar, bash has some idea of variables - specifically environment variables. You also know how to use these variables with the variable substitution syntax covered earlier - that is to access the value of the variable SHELL you would write $SHELL.

It is possible as well in a script to define variables that exist only while that script is executing. Let’s try that:

#!/usr/bin/env bash

target="foo"

my_first_command "$target"

my_second_command "$target"

Note the lack of spaces around the = in the declaration. Now we can define a value in one place and use it multiple times elsewhere!

Functions

Bash also allows you to define functions. We can use this to write some sequence of commands once and then execute them with different “arguments”. Let’s try that:

#!/usr/bin/env bash

mcd () {

mkdir -p "$1"

cd "$1"

}

mcd "foo"

mcd "bar"

Here we define a function mcd that makes a directory and then moves to it. Notice that we can use it like any other command available to us after we have defined it. Notice also the use of the variable 1. In bash, this refers to the first argument passed to a function. In the first case, it would expand to “foo”, but in the second it would expand to “bar”. This allows us to define our own custom commands within a script that are made up of the commands we already have!

Loops

There are cases where you may want to run a command or set of commands multiple times. Let’s see an example of that:

#!/usr/bin/env bash

for image in "*.png"; do

convert "$image" "${image%.*}.jpg"

done

Here we convert every PNG in the current directory to a JPEG. The "${image%.*}.jpg" syntax tells bash to take the variable “image” and trim off the file extension. Neat!

Conditional Statements

Finally, it is possible to conditionally run commands. Let’s give that a try:

#!/usr/bin/env bash

count="$(ls | wc -l)"

if [[ "$count" -gt 5 ]]; then

echo "That's way too many files!!!!"

else

echo "As you were!"

fi

Here, we’ve combined several features of bash. First, we list the files in the current directory and use wc to count how many there are. We use command substitution to assign this to a variable count. Finally, we use if combined with bash’s numerical comparators (in this case -gt, short for “greater than”) to decide which path to take.

A Final Note on Scripting

Shell scripting is a powerful tool that we’ve only touched on very briefly here. Shell is a terse but expressive language for manipulating your system, but it’s not always the best tool for the job. Remember that the shell you interact with and the language you write in shell scripts are one and the same. Finally, there are excellent resources online for shell scripting - many problems you might want to solve have likely been solved already!

Exercises

Aliases

-

Create an alias

dcthat resolves tocdfor when you type it wrongly. -

Run

history | awk '{$1="";print substr($0,2)}' | sort | uniq -c | sort -n | tail -n 10to get your top 10 most used commands and consider writing shorter aliases for them. Note: this works for Bash; if you’re using ZSH, usehistory 1instead of justhistory.

Dotfiles

Let’s get you up to speed with dotfiles.

- Create a folder for your dotfiles and set up version control.

- Add a configuration for at least one program, e.g. your shell, with some

customization (to start off, it can be something as simple as customizing your shell prompt by setting

$PS1). - Set up a method to install your dotfiles quickly (and without manual effort) on a new machine. This can be as simple as a shell script that calls

ln -sfor each file, or you could use a specialized utility. - Test your installation script on a fresh virtual machine.

- Migrate all of your current tool configurations to your dotfiles repository.

- Publish your dotfiles on GitHub.

Remote Machines

Install a Linux virtual machine (or use an already existing one) for this exercise. If you are not familiar with virtual machines check out this tutorial for installing one.

- Go to

~/.ssh/and check if you have a pair of SSH keys there. If not, generate them withssh-keygen -o -a 100 -t ed25519. It is recommended that you use a password and usessh-agent, more info here. -

Edit

.ssh/configto have an entry as followsHost vm User username_goes_here HostName ip_goes_here IdentityFile ~/.ssh/id_ed25519 LocalForward 9999 localhost:8888 - Use

ssh-copy-id vmto copy your ssh key to the server. - Start a webserver in your VM by executing

python -m http.server 8888. Access the VM webserver by navigating tohttp://localhost:9999in your machine. - Edit your SSH server config by doing

sudo vim /etc/ssh/sshd_configand disable password authentication by editing the value ofPasswordAuthentication. Disable root login by editing the value ofPermitRootLogin. Restart thesshservice withsudo service sshd restart. Try sshing in again. - (Challenge) Install

moshin the VM and establish a connection. Then disconnect the network adapter of the server/VM. Can mosh properly recover from it? - (Challenge) Look into what the

-Nand-fflags do insshand figure out a command to achieve background port forwarding.

Job control

-

From what we have seen, we can use some

ps aux | grepcommands to get our jobs’ pids and then kill them, but there are better ways to do it. Start asleep 10000job in a terminal, background it withCtrl-Zand continue its execution withbg. Now usepgrepto find its pid andpkillto kill it without ever typing the pid itself. (Hint: use the-afflags). -

Say you don’t want to start a process until another completes. How would you go about it? In this exercise, our limiting process will always be

sleep 60 &. One way to achieve this is to use thewaitcommand. Try launching the sleep command and having anlswait until the background process finishes.However, this strategy will fail if we start in a different bash session, since

waitonly works for child processes. One feature we did not discuss in the notes is that thekillcommand’s exit status will be zero on success and nonzero otherwise.kill -0does not send a signal but will give a nonzero exit status if the process does not exist. Write a bash function calledpidwaitthat takes a pid and waits until the given process completes. You should usesleepto avoid wasting CPU unnecessarily.

Terminal multiplexer

- Follow this

tmuxtutorial and then learn how to do some basic customizations following these steps.

Licensed under CC BY-NC-SA.